The Halmarks of a Classic Rosé de Provence

Rosé de Provence is the kind of wine that fulfills a longing for a particular time and place. Its pale salmon hue, fresh fruit aroma and tumbling minerality evoke seaside lunches and sunset aperitifs. Typically made from grenache, cinsault, syrah and mourvèdre, the classic style is light and refreshingly dry. When the weather begins to warm, Americans have an insatiable appetite for Rosé de Provence. For eight consecutive years this bottled essence of Southern France has experienced double-digit sales growth here. As such, today we have access to more rosés from a greater variety of Provençal producers than ever before.

Achieving the elegant simplicity of a well-crafted rosé requires gentle handling of mature fruit. Corners cut in the vineyard lead to thin wines with an aftertaste that can be green or medicinal, wines that are the bad oysters of summer drinks. Good rosés should be light-bodied with mouthwatering acidity and taste of white flowers, seashells and just-picked berries. A few bottles that fulfill this tall order are Château de Pourcieux, Domaine de Saint-Ser, Château la Calisse, AIX and Domaine de l'’Abbeye Clos Beylesse.

Rosé de Provence is not a wine to be sipped slowly and pondered. It is meant to disappear quickly, by the magnum if possible, and its charming way of capturing the spirit of Mediterranean idyll should be delivered to the consumer without emptying their wallet.

Salcheto’s Remarkable Winery

Inspired to improve his wines while reducing energy consumption, Michele Manelli, the winemaker at Salcheto in Montepulciano, Italy, has built a remarkable winery that is completely off the grid.

Nestled into the side of a hill with a vertical garden planted on its façade to absorb the sun, the winery is as beautiful as it is functional. The roof doubles as a piazza and is equipped with an automated sprinkler system. When the piazza is wet, the sun’s energy vaporizes the water and cools the winery through a simple (yet ingenious) thermodynamic process. The facility is heated by burning clippings and other materials in the local landscape. Inside, there are no light bulbs. Natural light is delivered through long reflective tubes and mirrors. To pump over, stainless steel vats harness the power of CO2 released during fermentation process. Electricity is provided through solar panels. In terms of metrics, the net result is that Salcheto’s winery uses 54% less energy than a conventional facility.

At this state-of-the-art winery, Manelli makes Obvius a Rosso di Montepulciano he describes as being made “exclusively from grapes.” For Manelli, this means no added sulfites, cultured yeasts, oak barrels or even electricity are used in the winemaking process. The recipe calls for perfectly intact sangiovese grapes, ambient yeasts and vinification in his stainless steel vats designed to harness CO2 to power the mechanism for pumping over. The wines are aged and bottled in an oxygen free environment. The result is a fresh juicy wine with a complex inner core, and a terrific value at $19 a bottle.

Stephen Carrier on Harmony in Mature Red Bordeaux

Few people understand what distinguishes the red wines of Bordeaux from their New World counterparts better than Stephen Carrier, the winemaker at Château de Fieuzal in Pessac-Léognan. The son of grape growers from Champagne, Stephen began his career as the winemaker for Newton Vineyard in the Napa Valley before honing his skills crafting Bordeaux blends at Château Lynch-Bages in Pauillac. Here he shares his passion for mature red Bordeaux.

Sophie Menin: What makes for a great red Bordeaux?

Stephen Carrier: In one word? Time.

SM: We’re surprised you didn’t say vintage or terroir.

SC: Bordeaux has sixty appellations each with a distinctive terroir. Every year the potential exists for great wines to come from the Medoc where the presence of clay gives the wines the potential to be bold and lush, or the exacting gravelly soils of Pessac-Léognan, or the merlot based wines of St-Émilion and Pomerol. But in all these regions, the young and old wines taste very different.

SM: How so?

SC: Young Bordeaux is like a bright child in need of a good education. It is alive with aromas of fresh fruit and spice. If you hold your nose to the glass, you will experience the heady scents of blackberries, red currants, tobacco and vanilla. I assure you that you will want to drink this wine, but I don’t recommend it. All you will taste are the building blocks of a wine that has not yet reached its potential. A wave of fruit will be followed by the drying sensation of tannins on your tongue and gums.

SM: What changes over time?

SC: With time the fruit flavor grows deeper, the tannins become silky and aromas of spice and earth begin to dominate the wine’s perfume. This experience of depth, harmony and balance is what great Bordeaux is all about. Depending on the vintage, this transformation can happen after five, ten or twenty years in the bottle.

Many wines go through an intermediate stage when the tannins have softened and integrated into a wine that still possesses the expressive bloom of fresh fruit. I like these wines very much as well.

SM: What do you drink when you are waiting for the wines to mature?

SC: In France we drink the less celebrated vintages while we are waiting for the great ones to come around. Many of the less celebrated years produce wines with more delicate fruit. These wines are less tannic and mature earlier. Right now, the 2007s are very good!

The Vogue for Amphorae

Winemakers and fashion designers share the habit of combing styles and techniques from the past with an eye toward improving their current works. For designers it might be a skirt length, stitch or fabric. These days, for winemakers, it is often the use of clay vessels called amphorae.

Amphorae are ceramic vessels that were used by the ancient Greeks for the storage and transport of wine, as well as other liquids and dry goods. Typically, they have a large oval body, a narrow cylinder-shaped neck, two handles and a pointed base. The average height of amphorae is eighteen inches, but they could be as tall as five feet.

What attracts winemakers to amphorae? In a word: purity. Like steel, clay is flavor neutral, and like oak, it allows for the beneficial passage of tiny amounts of oxygen. Winemakers who swear by the use of amphorae believe it expresses the unique characteristics of the grapes without adulteration.

Amphorae wines tend to be darker and cloudier than their counterparts made in steel or oak. The best have the same kind of inner complexity you expect of a deep satisfying broth. They are popular with the natural wine movement because the types of corrections that happen in a modern cellar are not possible with these wines. Their deliciousness depends entirely upon impeccable practices in the vineyard.

The use of amphorae in winemaking dates back 6,000 years to the Republic of Georgia where their contemporary, distinctive orange-colored wines are still made in beeswax-lined, terra-cotta amphorae, called quervi. The ceramic containers are buried up to their necks in the earth while the wines macerate and ferment.

If you subscribe to the notion that everything old is new again, we recommend giving amphorae wines a try. Some notable producers are Elisabetta Foradori in Alto Adige, Italy; Josko Gravner in Fruili, Italy; Movia in Slovenia; C.O.S. and Frank Cornelissen in Sicily, Italy; and Beckham Estate in Oregon, where the winemaker is a ceramics instructor who makes his own vessels.

Summer Reds

When we talk about white wines for summers, we implicitly understand the reference. Summer whites are bright, light, thirst quenching wines that are eminently drinkable. Sancerre ,Muscadet Sevre-et-Maine and Albariño immediately come to mind. Summer reds are more difficult to define. We know we are not breaking out a pensive vintage Bordeaux for the family barbeque or uncorking a luscious California cabernet sauvignon with a bowl of chilled asparagus soup, but it is it possible to reduce the entire universe of reds to a simple rule of thumb for the summer months?

One helpful idea is to think about the climate of the wine’s region of origin. Warm climate reds tend to be juicy with plenty of body and just enough acidity to be mouthwatering. Think nero d’avola from Sicily, malbec from Mendoza, or grenache from the southern Rhone Valley. These intensely flavorful wines will maintain their structure in the face of bold, smoky, spicy summer fare.

On the other end of the spectrum are the cool climate reds, what we call bistro wines, since they show so well served lightly chilled by the carafe. At their best, cool climate reds are youthful and delicious, tasting of fresh berries often with floral or mineral notes. They won’t overwhelm a fresh salad niçoise, spring pea soup or chicken paillard. Some very fine examples can be found in the Loire Valley, notably the cabernet franc from Chinon and Saumur. Other sources worth seeking out are pinot noirs from Alsace and Central Otago.

The New California Wine

In 2010, San Francisco Chronicle wine editor Jon Bonné was writing a short article for Saveur when his editor called him with a problem. She had a slew of stories about California wine that were not fitting together and needed an overarching narrative to connect them. She gave him a week to develop and write the piece. After seven days with little sleep, it was clear that what had once seemed like a disparate movement of iconoclastic producers had reached a critical mass and a new kind of California wine had emerged. The seismic shift begged for more space than a special edition of a magazine could offer, thus his indispensable volume The New California Wine: A Guide to the Producers and Wines Behind a Revolution in Taste.

Sophie Menin: What are the New California Wines?

Jon Bonné: These wines represent the continuity of the state’s long wine growing history, what made people fall in love with California a generation ago and where it is going. They are wines made in a style that is relevant to wines around the world, wines that have a sense of place and are meant to be part of a gastronomic experience. They often use varieties other than the northern European grapes to which we’ve grown accustom and are not trapped in a bigger is better arms race.

SM: Yet not all the wine and winemakers discussed in the book are new.

JB: The book’s theme may be the new generation of winemakers, but it was important for it not to be about just the young and hip. Decades ago, winemakers such as Paul Draper, Cathy Corison and Ted Lemon (respectively of Ridge, Corison and Littorai) chose to stick with values they deemed important and pursued a radically different set of questions as others took an easier path. Their work wasn’t simply to make great wine, but to push ahead an industry that was really in its infancy.

SM: What have you discovered about where varietals are doing well?

JB: Grenache and grenache blanc are going to be superstars. Red Grenache grows beautifully in Santa Barbara, Santa Rita and the high dessert. The Sierra Foothills are a largely untapped resource for native Rhone varieties, especially the whites. Ron Mansfield is the great pioneer of those grapes up in mountains.

SM: Why is table wine such a dilemma in California?

JB: For all the quirky things people are doing, the core of the industry is not paying attention to simpler wines so table wine is left to those who make wine as an industrial product. The new winemakers seem to understand that even if you make great wine, you still have a responsibility to make a simpler wine as well. Steve Matthiasson is an example of someone who is pushing forward on this issue. With the Tendu project he is making aggressively priced compelling wines in liter bottles with crown caps. The white is mostly vermentino from Yolo County and he just released a red made from aglianico.

SM: Has it been helpful to not be a California native when reviewing for the San Francisco Chronicle?

Ten years ago, when I began writing for the San Francisco Chronicle, coming from New York seemed like a liability. It was easy for some in the industry to dismiss me as a dude from New York who says wine should be made in a European style. But more relevant than being from New York was that I had just spent five years writing about wine in in Washington State where it was natural to meet talented winemakers without big money behind them. Washington State winemakers constantly have to prove themselves. It gave me an innate understanding of the type of winemakers covered in this book.

What to Drink with a Dish that is Intriguing, Sophisticated, and Bitter....

In the introduction to Jennifer McLagan’s fascinating new book, Bitter: A Taste of the World’s Most Dangerous Flavor with Recipes, the author imagines her subject through the lens of the Japanese word for bitter tanginess, shibui.

First she quotes a Kinfolk Magazine article that explains, “When people are described as shibui, the image is of a silver-haired man in a tailored suit, with a hint of bad-boy aura about him.” Then she says, “So bitter is a cultured, intriguing, and sophisticated taste, with a dangerous side. Who could be more fun to cook or dine with?”

Regardless of whether or not you care to break bread with a shibui gent, the question of what to drink when enjoying a dish that is intriguing, sophisticated, and bitter is not at all obvious. Bitter comes in many different guises: grapefruit, olives, artichokes, kale, couscous, and cocoa are all bitter, but taste very different.

The challenge is finding wines that bringing a sense of balance and harmony to a particular dish. Here are a few examples:

The fresh apple and mineral flavors in a young Austrian grüner veltliner like the 2012 Sohm & Kracher go beautifully with white asparagus or bitter citrus, such as Seville oranges.

The hint of sweetness and mouthwatering acidity in a German riesling such as the 2013 Donnhoff Estate rounds out the bitterness in Brussels sprouts and brightens the flavors of many of its tastiest roasting partners, for instance bacon and chestnuts.

The mix of dark berries and woodsy notes in a Rosso di Montalcino like the Il Poggione showcase the smoky bitterness of grilled radicchio drizzled with aged balsamic vinegar.

Even a luscious fruit-forward Napa Valley cabernet sauvignon such as the Chateau Montelena has a touch of bitterness at its core, making it the perfect foil for the most decadent of bitter desserts, molten dark chocolate.

Rosé Champagne

When Belinda Chang, a James Beard Award winning wine director wrote the wine notes for Charlie Trotter’s Meat and Game, her biggest takeaway from the many weeks of sampling bottles in Trotter’s enviable cellar was this: the perfect wine for a dish is often completely the opposite of what you think it should be! Rosé Champagne and dry aged steak is a great example of this maxim.

Traditionally, Champagne is a white sparkling wine made by bottling a base wine made of white grapes (chardonnay) and two red grapes (pinot noir and pinot meunier) that are pressed gently so that no color is extracted from their skins, then adding a liqueur de tirage, wine mixed with sugar and yeast. The liqueur de tirage initiates a second in-bottle fermentation resulting in Champagne’s distinctive effervescence.

Of course, there are variations on the theme, a Champagne labeled blanc de blancs will be one hundred percent chardonnay. A Champagne labeled blanc de noirs will be entirely pinot noir and pinot meunier, though it will still be a white sparking wine. Then there are the rosés.

Rosé Champagnes are generally made by adding a small amount of red wine to the base. Their colors can range from delicate salmon to ballerina slipper to hot pink, depending on how much red wine is present. When a rosé is also a blanc de noirs, its hue is achieved by letting the base wine absorb color from the dark skins until it turns pink. But the wine is drained off the skins or “bled” before the color grows too deep. Both methods yield Champagnes with more structure, intensity and earthy flavors than the traditional blends. These qualities along with Champagne’s naturally high acidity make rosé Champagne a terrific foil for rich meats.

When pairing a rosé Champagne with a dry aged steak, Belinda recommends looking for houses whose rosés demonstrate development and richness over fresh fruit. Veuve Clicquot was the first house to commercially export rosé Champagne and still makes a very successful style that works with a savory steak cut. Chartogne-Taillet Champagne Rosé and Gatinois Brut Rosé are two of her other favorites for a meat centered feast.

There are certainly several styles that pair beautifully with a dry aged steak!

Cloudburst Reveals the Potential of the Margaret River

Cloudburst owner and winemaker Will Berliner just netted the chardonnay he will harvest in late February. The meshwork protects the fruit from three types of birds: silver eyes, which take a sip out of each berry; ring neck parrots, which lop off whole grape bunches to exercise their beaks; and honey birds, which actually eat the fruit. He guards his tiny crop jealously, given that after three vintages, Cloudburst Chardonnay has earned coveted placement on the wine lists of three New York City dining meccas-- Tribeca Grill, Le Bernardin, and Eleven Madison Park, a remarkable accomplishment for a novice winemaker with a vineyard in the Margaret River of Western Australia.

Cloudburst’s unlikely genesis began with Will’s homesick Australian wife, Ali, with whom he used to travel to Australia regularly to visit family. When Ali became pregnant and sleeping on floors was no longer possible, they drove the Australian coast in search of a home. Coming from New England, Will found it difficult to imagine living in the country’s arid climate. Then they visited the Margaret River, a wine community among ancient hardwood forests five miles inland from the point where the Indian and Southern Oceans meet, and it just felt right. They spent their savings on a property abutting Aboriginal land and a national park, which also happened to be on the local wine route near the well-known wineries Leeuwin Estate and Moss Wood Winery.

For seven years, Will listened to the land and developed a deep affinity for biodynamic practices. Meanwhile, he studied viticulture long-distance at the University of California at Davis, educated his palate and began planting experimental blocks of chardonnay and other varieties. He released the first vintage of his expressive chardonnay in 2010, followed by a leaner, more complex bottling in 2011 and an elegant, fleshier wine 2012. All in all, it is an auspicious debut for an adventurous spirit from Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Some Unexpected Advice for Maintaining a Healthy White Smile After Drinking Red Wine

While there is nothing quite like the pleasure of indulging in an inky red wine with great structure and mature fruit, too often the smile of satisfaction that ensues takes on a purple hue.

This may seem like the perfect time to sneak off to the bathroom for a quick brush, but dental professionals recommend you to hold off! The acidity in wine weakens the enamel on your teeth, making them extra-sensitive to the scratchy strokes of a toothbrush. To protect your teeth, wipe the stains away with a damp piece of gauze and wait at least an hour before brushing so that your saliva has time to rebalance the pH in your mouth.

Here are a few more tips for indulging in the great red wines of the world while maintaining a healthy white smile.

1. Brush and rinse well before you drink. Wine sticks to the plaque on your teeth.

2. Drink plenty of water between sips, preferably with bubbles, to rinse away stains.

3. Nibble on hard cheese. Cheese helps increase saliva production, which balances your mouth’s pH. It also adheres to enamel, protecting your teeth from acid’s corrosive effects.

4. Brush and floss and before going to bed.

There is, of course, always a silver lining. The polyphenols in red wine actually block the ability of the bacteria that causes tooth-decay to stick to your teeth. For optimal enjoyment and oral health: take a bite of cheese, drink red wine, hydrate, drink again and repeat. When the meal or party is finished, wait an hour before you brush your teeth so that the pH in your mouth has time to rebalance and you won’t damage your enamel.

“You taste and you taste and you taste until you see the light!”

How does one understand Burgundy? According to Jacques Lardière, who spent forty-two years as Louis Jadot’s technical director before officially handing the reigns to Frédéric Barnier in 2012, “You taste and you taste and you taste until you see the light!” It’s a deceptively simple aphorism that cuts through the usual wine jargon to underscore the essential truth that a wine can only be known through your senses – seeing the color, smelling the aromas, tasting the wine and experiencing how it feels in your mouth.

Sampling enough Burgundy to begin to know the wines requires a strategy for sourcing bottles that are both affordable and compelling. Wine from the high-integrity producers in Burgundy’s southern appellations, the Mâconnais, Côte Chalonnaise and Beaujolais, are an excellent place to start. The Domaine Leflaive Mâcon Verze is a chardonnay of exceptional complexity and finesse. The Domaine Francoise & Jean Raquillet Mercurey exhibits the classic wild strawberry and violet aromas associated with Burgundian pinot noir. The Cru Beaujolais of Stéphane Aviron are lucid expressions of vineyard site. When choosing wines from marquee villages on the Côte d’Or, the négociants Louis Jadot and Joseph Drouhin consistently offer value and quality, both are major landowners throughout Burgundy and leaders in organic and biodynamic practices.

Women in Wine: The Young Guns

For the latest generation of women winemakers, there has been no single path to success. The spectacular career of Ntsiki Biyelais a case in point. Raised in the rural South African province KwaZulu-Natal, Ntsiki Biyela had never tasted a sip of wine before South African Airlines offered her a full scholarship to study oenology in Stellenbosch. Afterwards, in 2004 she joined STELLEKAYA as a junior winemaker, where she was given responsibility for the entire cellar a year later, becoming the first black woman and first Zulu in South Africa to hold the title head winemaker. It was a bold choice for the winery, but a wise one. In 2009 the agricultural magazine Landbouweekblad named Biyela South Africa’s Woman Winemaker of the Year.

Oenology school followed by travel has been an effective formula for the young, talented and ambitious. After studying at Lincoln University in Christchurch, New Zealand, and working stints in the Margaret River of Australia and in Sicily, Italy, Tamra Washington was invited to return home to Marlborough, New Zealand, to launch YEALANDS ESTATE WINES. Molly Hill studied at the University of California at Davis then cut her teeth at DOMAINE CARNEROS and SEA SMOKE before becoming the winemaker at SEQUOIA GROVE in the Napa Valley. Renae Hirsch spent a decade acquiring skills at wineries across the globe before being offered a position at the helm of HENRY’S DRIVE in Padthaway, Australia.

In recent years, young women vintners have earned distinguished international reputations as leaders in minimalist winemaking, as witnessed by the fine wines produced and the acclaim bestowed upon Arianna Occhipinti of OCCHIPINITI in Sicily, Italy; Magali Terrier of DOMAINE DES 2 ANES in the Languedoc-Roussillon, France; and Nadia Verrua of CASCINA TAVIJN in Piedmont, Italy.

It seems counterintuitive, but women born into the world’s most prestigious wine making families often have to work the hardest to prove themselves worthy of a hand in cellar. Alix de Montille of DOMAINE DE MONTILLE in Burgundy, France, was required to study law before earning her diploma in oenology. Today she crafts the white wines for DOMAINE DE MONTILLE and MAISON 2 MONTILLE, the boutique négociant label she established with her brother. María José López de Heredia earned degrees in both law and theology before learning viticulture and winemaking. She is now the general manager of her family’s venerated Rioja estate R. LÓPEZ DE HEREDIA. And in perhaps the world’s longest audition for the role, fourth generation Argentine vintner Laura Catena graduated magna cum laude from Harvard University then earned a degree in medicine from Stanford University before becoming part of the winemaking team at BODEGA CATENA ZAPATA, her family’s winery in Mendoza, Argentina, where she is now general manager.

A Valentine's Day Ode to Amarone

Why drink Amarone on Valentines Day? Have you ever stared at a glass of this classic Italian wine from the Veneto, the land of Romeo and Juliet? Its blood red hue --achieved through fermenting dried corvina, rondinella and molinara -- is the color of passion, desire, seduction and thirst. It clings to the side of the glass when you give it a swirl. If you allow your nose to hover over the glass’s bowl, it is filled with aromas of plums, chocolate, black pepper, espresso and earth. Then there is the name, Amarone, (pronounced: a-mar-oh-nay), which sounds so close to amore, the Italian word for “love,” but actually has its roots in amaro, the Italian word for “bitter,” as if to remind us that the two feelings almost always come in pairs. Plus, if you handle Amarone with care, the best bottles will last a century or more.

While I can’t help you find the perfect mate, or even Valentine’s Day date, in recent years it has gotten much simpler to pick a terrific Amarone. In 2011, after decades of overproduction that led to vastly uneven quality among estates, twelve top-tier producers banded together to create an association called the Amarone Families, dedicated to excellence and the preservation of region’s distinctive artisanal winemaking traditions. These producers are voluntarily holding themselves to stricter standards than required by the DOCG. The families include: Allegrini, Begali, Brigaldara, Masi, Musella, Nicolis, Speri, Tedeschi, Tenuta Sant’Antonio, Tommasi, Venturini and Zenato.

If you don’t remember these names, all bottles of wine produced by the Amarone Families are all marked with a hologram of the letter “A”. There is an adage in wine that you can judge a producer by the quality of their entry-level offerings. This is particularly true of the Masi Costasera, Tenuta Sant’Antonio Selezione Antonio Castagnedi and all the producers who founded the Amarone Families.

Wines for Marcus Samuelsson’s New American Cuisine

At Marcus Samuelsson’s iconic Harlem restaurant, Red Rooster, culinary director Joel Harrington executes New American Cuisine, defined as flavors representative of the vast mosaic of cultures and ethnicities that constitute the fabric of America. For Samuelsson, these foods are also a highly personal expression of the ethnic and cultural influences in his own life.

Born in Ethiopia, Samuelsson lost his parents to tuberculosis and subsequently was adopted by a couple in Sweden, where he discovered his passion for cooking in his grandmother’s kitchen. His early career took him on jaunts throughout Europe, Asia and the Americas to study and work, until he became one of the most celebrated chefs of his generation. Samuelsson has earned three stars in The New York Times as the chef at Aquavit; won Top Chef Masters in Season Two; prepared the meal for the first State Dinner of the Obama administration; and published the memoir Yes, Chef!

When it came to designing a wine list that would straddle gravlax and jerk chicken, oysters Rockefeller and blackened catfish, his first priority was seeking out accessible wines that go well with a wide variety of foods. Toward this end, the Red Rooster list features an impressive array of pinot noirs in styles spanning from overtly fruity to delicate and textured. A current favorite among guests and staff members is the OPP (Other People’s Pinot) from Mouton Noir, the Dundee, Oregon winery owned by the sommelier André Hueston.

In terms of bolder reds, the Ridge, petite sirah is the go-to recommendation for the steak-for-two and Caribbean pork chop. Recently, more South African wines, such as the Raats, Western Cape, cabernet franc, are making their way onto the list in honor of the memory of Nelson Mandela.

The Elegance of Churchill’s Dry White Port

The question of what to drink as an aperitif on a winter night, when the thought of something cold, light and crisp sends chills up your spine, is not easily solved. In Portugal, the answer is often white port served lightly chilled. This is a great idea, in theory. It is easy to imagine sitting by a fire sipping a well aged fortified white wine that warms you from the inside as flavors of honey and almonds fill your mouth. Unfortunately, most white ports fall into the category of one-dimensional high alcohol sweet wines that are best when served combined with other ingredients by a talented mixologist.

This backdrop is what makes tasting Churchill’s Dry White Port a bit of a revelation. Though it is labeled “dry aperitif”, Churchill’s drinks like a fine tawny that happens to be made from white grapes. The base wine is a field blend of local white varieties — Malvasia Fina, Códega, Gouveio and Rabigato— harvested from an old high-altitude vineyard in the Douro sub-region of Cima Corgo. This means the grapes are grown and pressed together before being fermented dry. Once it is fortified, the port is aged for ten years in oak casks. The result is a complex dry white port with a golden hue. In the mouth, it is viscous with nutty flavors and mellow fruit. It pairs beautifully with roasted almonds, smoked salmon, paté, gougéres as well as most cheeses, and its consumption need not be limited to the winter season. Once opened, it will keep in the refrigerator for a month.

Jasmine Hirsch: In Pursuit of Balance

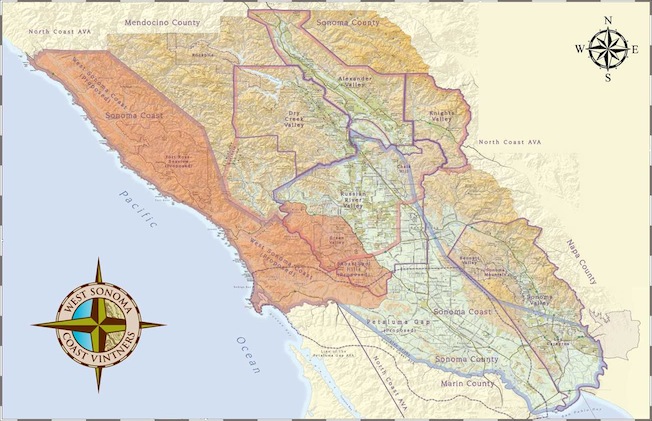

Jasmine Hirsch says she discovered wine while living and working in New York. This may sound improbable considering she grew up at Hirsch Vineyards, the oldest premium pinot noir vineyard in the West Sonoma Coast, but she explains, “My dad was a grape grower. He started making wine after I went to college.”

She quickly developed a passion for wines with finesse and restraint, especially collectible Burgundy and the rieslings she tasted at Terroir. When she returned to Sonoma to work with her father, Jasmine wondered whether it was possible to make the kind of pinot noir she had grown to love in California. She put the question to Rajat Parr, wine director of the Mina Group and partner at Sandhi, who took out a pen and began writing the names of artisan pinot noir producers on a cocktail napkin. Thus, In Pursuit of Balance was born.

In 2011, Jasmine and Raj organized a group tasting of those wineries at RN74. Four hundred people showed up. The next year they added chardonnay to the roster and held an additional tasting at City Winery in New York. Within a couple of days, it sold out. Now in its fourth year, the annual In Pursuit of Balance tasting has become a reference point for talking about the breadth of styles and growing sophistication of California wine. Participating wineries are chosen in a blind tasting by committee. The only requirement is that they are made in California.

This spring, Jasmine and Raj will travel to London and Stockholm with Jon Bonné, author of The New California Wine, and several winemakers featured in the In Pursuit of Balance program. It is an international road show aimed at breaking the stereotype of California wines as being overly ripe and oaky.

After only a few years in the industry, Jasmine Hirsch has translated her ardor for pinot noir into a vital conversation about the evolving identity of the California wine scene.

A Room with a Barolo View

During the Middle Ages, the hilltop towns of La Morra and Barolo fiercely disputed who controlled the prime vineyard lands of Cerequio, one of the most prestigious of Barolo’s crus, or most important parcels of land. Today there is no doubt. Michele Chiarlo, along with his sons Stefano and Alberto, farm almost two-thirds of the nebbiolo vines planted in Cerequio’s calcareous Sant’ Agata marl – vines that yield Barolo wines of particular elegance and finesse with concentrated aromatics that lace ripe berries with dark chocolate and pleasing hints of eucalyptus.

A few short years ago, the Chiarlo family opened Palas Cerequio, a boutique hotel in the center of its eponymous vineyards. The hotel is a sanctuary for those who aspire to understand the wines of Barolo thoroughly. Consistent with the local architecture, from a distance it looks like a small cluster of houses. In the lobby are stones from each of region’s grand cru sites.

The rooms mirror the Chiarlo’s winemaking philosophy: balancing tradition and modernity, preserving the time-honored characteristics of Barolo while embracing practices that render the wines more sumptuous, less austere. Thus the whimsical Baroque style of the four suites in the historic manor nod to the past, while the remaining five suites, compositions in stone and oak with massive picture windows, look to the future. All are equipped with private spas, stacks of books and musical selections specifically chosen to prime guests for an expansive sensory experience once the wine is opened.

Which brings us to the Caveau of Cerequio, the hotel’s cellar where guests can sample the entire Chiarlo portfolio alongside Barolo from other regional luminaries such as Gaja, Boroli and Vietti. It is an ideal tasting environment: temperature controlled with a long table set above a floor lit to ensure a true reading of each wine’s hue.

The hotel will also arrange truffle hunts, castle tours and reservations at authentic Piedmontese restaurants such as the Michelin starred Antica Corona Reale and San Marco Ristorante. Short of renting a staffed villa, Palas Cerequio is perhaps the most exquisite way to experience what is like to live among Barolo’s vineyards.

Michele Chiarlo Barolo Cerequio is the perfect accompaniment to roasted or braised meats, such as this recipe for braised veal shanks.

Chablis: Chardonnay for Champagne Lovers

If you gravitate toward Champagne and Sancerre and prefer your chardonnay without overt flavors of oak, vanilla or butter, try Chablis. The eponymous wine of the most northerly appellation in Burgundy, Chablis is pure unadulterated chardonnay cultivated in Kimmeridgian limestone, a type of ancient (Kimmeridgian period) soil containing fossilized seashells. Combining the juiciness of the chardonnay grape with the fresh dry mineral qualities of wines from Sancerre or a Champagne Blanc de Blancs, the wines are delicious without being showy.

There are four levels of Chablis: Petit Chablis, Chablis, Premier Cru and Grand Cru. The wines grow weightier and more complex as they scale the hierarchy. A good quality Petit Chablis, such as Domaine Seguinot-Bordet, tends to be refreshing with citrus and mineral flavors. Wines at the Chablis and Premier Cru level, such as Domaine Romain Collet Les Pargues, have more weight, body and structure, yet retain all the liveliness and gripping mineral flavors of their siblings. In recent years, young producers like Thomas Pico of Domaine Pattes Loup have brought organic and biodynamic practices to the region resulting in Chablis’ of remarkable clarity of flavor. Meanwhile, Grand Cru Chablis, such as the Domaine Christian Moreau Père et Fils Chablis Grand Cru Valmur are among the world’s most age-worthy white wines. Not only do they develop attractive almond and caramel flavors after a few years in the bottle, once opened, the wines evolve in the glass in a way normally associated with Burgundy’s best pinot noirs, growing richer and more nuanced with each passing hour.

Because of its high acidity and restrained fruit character, Chablis is an extremely versatile food wine. It makes for a delightful aperitif served with fresh goat cheese or a nutty hard cheese such as Emmental. It holds up well in the face of salad dressing and asparagus, and will enhance any meal that features oysters, seafood, poultry or pork.

Clovis Taittinger on Opening Champagne

For Clovis Taittinger, 34, the welcome hiss of a Champagne bottle opening is always something magical. He still stares at the bubbles rising in his flute with awe. He views removing the signature mushroom-shaped cork from a bottle of Champagne as a ceremony of sorts and wants people to experience pleasure, not fear, when opening a bottle. Asked to advise those of us who did not grow up in one of Champagne’s most renowned family-owned Houses of an elegant and festive way to uncork a bottle, he shared his thoughts on what makes for the most graceful presentation:

1) Take your time. Move slowly. Concentrate.

2) Remove the foil.

3) Keep pressure on the cork while twisting the key of the Champagne’s wire cage six times to the left. Discard the cage.

4) Cradle the body of the bottle in your dominant hand as you wrap your other hand around the neck and the cork, to prevent the cork from flying off.

5) Holding the bottle upright at a slight angle, turn the bottle until the cork pops off into your hand.

6) If successful, the pop of the cork should sound like a gunshot with a silencer.

Mastery comes with practice, says Clovis. This Christmas he will practice at home with his wife, parents, children and a bottle of Taittinger’s Prestige Cuvee--Taittinger “Comtes de Champagne.”

Second Time Around: Thanksgiving Leftovers & White Rhones

Thanksgiving leftovers are one of the best meals of the year. Stuffing tastes better the next day as does gravy, homemade cranberry sauce and sweet potato soufflé. Some like to refresh the meal a bit by using the turkey carcass to make a rich soup, but for those who can’t look at the stove after all the holiday prep, a new wine pairing will do the trick.

Roasted turkey with gravy involves caramelized skin and dark rich sauce, which means that it calls out for a wine with some weight, aromatics and refreshing acidity. For The Big Meal the tried and true choices are pinot noir, cru Beaujolais and, for those who prefer something associated with America, zinfandel. Leftovers are a time to be more adventurous.

Once the guests are gone, why not try a white Rhône marsanne-roussanne blend? These age-worthy medium-bodied wines are a staple of the southern French table. Marsanne-roussanne blends combine marsanne’s weight and structure with roussanne’s bright acidity along with its honey, floral and mineral flavors. At their best, these wines possess great finesse. They run the gamut from great values from top domaines, such as the Domaine François Villard “Version” Saint Peray, to delicious splurge-worthy bottles, like the Jean Luc Columbo “Le Rouet” Blanc Hermitage. Look for producers from Hermitage, Saint-Joseph and Saint-Peray.

- Alsace

- Amarone

- Architecture

- Assyrtiko

- Australia

- Austria

- Barbaresco

- Biodynamics

- Bolgheri

- Books

- Bordeaux

- Burgundy

- Cabernet Franc

- Cabernet Sauvignon

- California

- Champagne

- Chardonnay

- Chinon

- Cinsault

- Collecting

- Cycle of the Vine

- Dolcetto

- Entertaining

- France

- Gadgets

- Gigondas

- Greece

- Grenache

- Grüner Veltliner

- Holidays

- Hotel

- Importers

- Israel

- Italy

- Kamptaland

- Kosher

- Loire Valley

- Medoc

- Merlot

- Mouvedre

- Napa

- Nebbiolo

- Nero d'Avola

- News

- Pairings

- Pessac-Léognan

- Piedmont

- Pinot Noir

- Pomerol

- Pommard