Rosé and a Garden Bench

You can drink rosé any time of the year, but part of its appeal is an association with the months when warmth and light are abundant, colors more saturated, and oceans become swimmable instead of foreboding. The brevity of the season brings with it an intensity and awareness that it is not to be squandered or missed. This connotes something different to everyone - for me, it's dinners in our city garden.

When our building needed a new roof, we had to pull our garden up. It was a timeworn treasure of sea grass, lavender and roses hauled from the greenmarket, a place where we eked out extra seasons from aging cedar planters with wood planks and metal brackets. The new garden is a different species entirely. It’s up to code, approved by engineers, and it can be dissembled and reassembled at will. It’s exquisite, although we miss the well-worn character of the improvised.

While we were rebuilding, I read a book by the Belgian designer and antiquarian Axel Vervoordt called Wabi Inspirations, about the influence of Wabi aesthetics on his work. Wabi philosophy comes from Zen monks who sought solace and contentment in simplicity and restraint, monks who valued the beauty of imperfect objects in their most austere and natural state. Moved by the tranquility of Vervoordt’s spare reflective residential spaces, I contacted the gallery about a Wabi garden bench. The images they sent suggested the aesthetic of the humble and decaying was not limited to objects from the East. It could also be found in a Spanish wedding bench, a French pew, or the 18th century Piedmontese farmhouse bench that now resides in our garden. The garden’s porcelain tiles and the bench are precisely the same color, but that is where their similarities end. One is the result of talented engineers replicating the look of aged cedar; the other exudes the kind of gravitas that comes from centuries of weathering the elements, evidenced in its irregular veins and raw edges. The difference in the materials brought to mind how we measure quality and character in rosé wines, a category where color is often the only common denominator.

As with Wabi objects, the best rosés convey simplicity and refinement. They are unpretentious, yet have a story to tell, one with a beginning, middle and end. It might open with aromas of citrus and red berries, then offer a whisper of an impression of fruit on the palate, followed by a wave of refreshing acidity, and a long finish that speaks of either sea or stones, depending on where the vineyard is located. The wines will reflect their fruit source. A rosé made from pinot noir grown in Sancerre might be delicate, while one made with mouvèdre from Bandol is likely to be full of interior architecture.

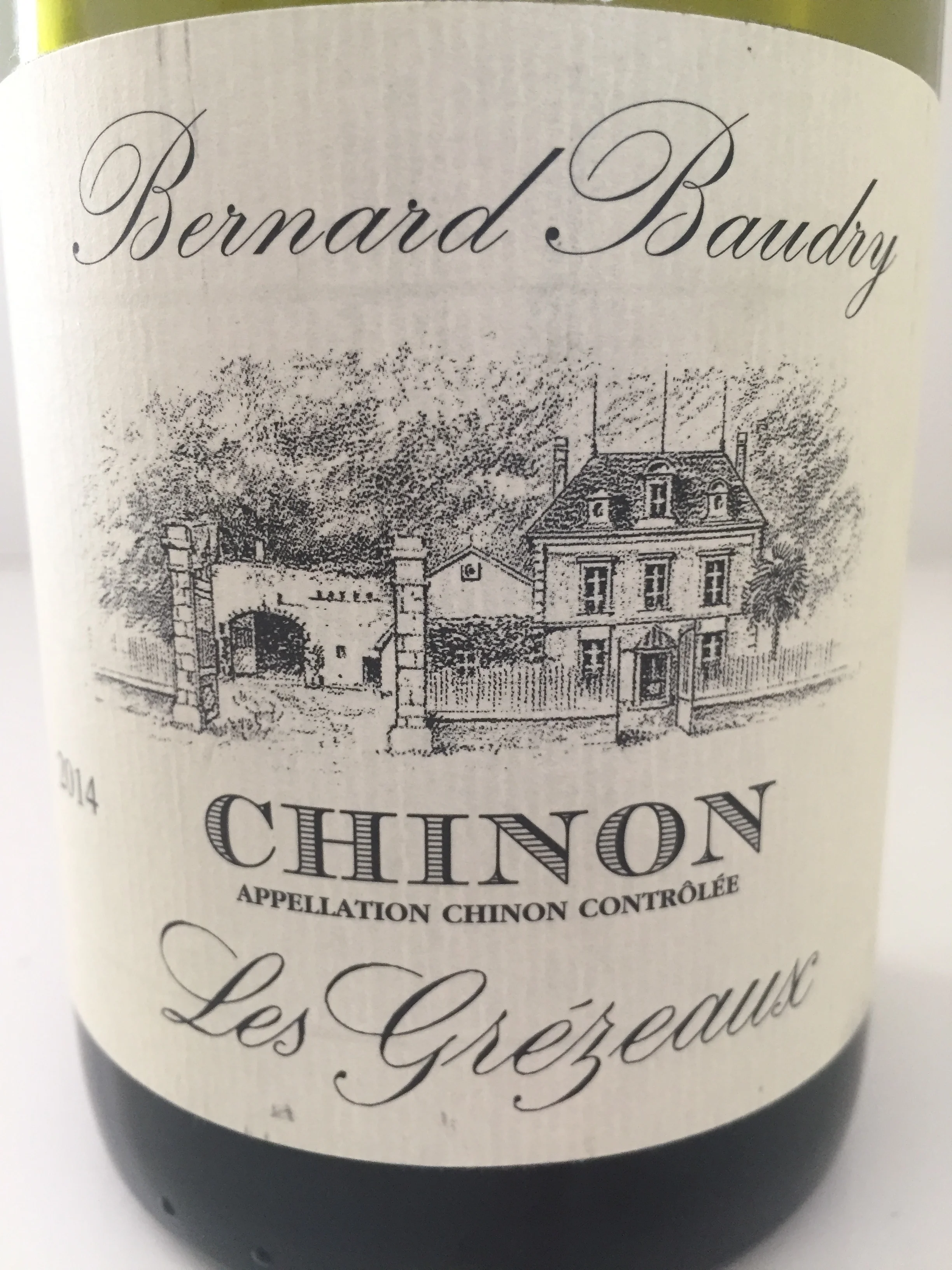

Daniel Ravier, the winemaker at the iconic Bandol estate Domaine Tempier once told me that making rosé is easy, but making good rosé is very difficult. This is because what distinguishes a rosé is not the region, grape variety, or price, but the scores of small decisions made in the vineyard and the cellar long before the bottle is opened. Even though certain coastal enclaves have burnished the image of rosé as essential to summer idle, there are pockets of excellence the world over: Domaine Bernard Baudry in Chinon, Chateau de Trinqueverde in Tavel, Finca Torremilanos in Ribera del Duero, Robert Sinskey Vineyards and Matthiasson in the Napa Valley, to name a few standouts.

In Provence, exceptional examples abound from jewel box wineries such as Clos Cibonne along the coast, Domaine de l’Ile on the island Porquerolle, Saint Ser at the foot of Mount Sainte Victoire, and Domaine Tempier. Beware of popular brands that have increased production exponentially rendering the wine you fell for a decade ago less than delicious. Exports from the region to the U.S. have experienced annual double-digit growth for more than twelve years. Some producers have cashed in on the strong trend at the expense of quality. Also, if a rosé smells of marshmallow, candy, pineapple or banana, or if after the first sip you perceive a chemical taste or hollowness where the flavor should be, throw it out. It’s either made from inferior fruit or has been manipulated in the cellar. Once you do find a rosé that pleases you, stock up early. The coveted ones disappear quicker than June roses.

When it's warm outside, I pair rosés with simple no-cook dinners, such as beef carpaccio inspired by the Roman chef Sandro Fioriti. Ask your butcher to slice beef tenderloin into carpaccio. Arrange the carpaccio in a single layer on individual plates or a large platter. Top the beef with generous portions of shaved parmesan, shaved celery, and finely sliced cremini mushrooms. Finish the dish with salt, pepper and a drizzle of olive oil , and serve it with your favorite market salad and crusty bread.

Wishing you a peaceful summer.

10 Rosés

The Quiet Nobility of Chinon

If wines had seasons, late autumn would be the time for Chinon. Earthy, juicy, tannic, brooding, and elegant with age, these wines taste of the moment following the harvest when the work of producing fruit is done and the vines are soaking in the last of the warm autumn sun before leaves fall, wood hardens, and sap descends to their roots.

The wines are one hundred percent cabernet franc, a thin-skinned, aromatic, black grape best known for its opulent star turn further south in Saint-Émilion, particularly in the hallowed cellars of Chateau Cheval Blanc (ten percent cabernet sauvignon is permitted in Chinon, but rarely included in the blend). Cabernet franc-based wines from Chinon may not be as overtly sumptuous as those from a Grand Cru Classé Bordeaux, but the best examples can be equally noble, if quietly so.

If wines had seasons, late autumn would be the time for Chinon. Earthy, juicy, tannic, brooding, and elegant with age, these wines taste of the moment following the harvest when the work of producing fruit is done and the vines are soaking in the last of the warm autumn sun before leaves fall, wood hardens, and sap descends to their roots.

The wines are one hundred percent cabernet franc, a thin-skinned, aromatic, black grape best known for its opulent star turn further south in Saint-Émilion, particularly in the hallowed cellars of Chateau Cheval Blanc (ten percent cabernet sauvignon is permitted in Chinon, but rarely included in the blend). Cabernet franc-based wines from Chinon may not be as overtly sumptuous as those from a Grand Cru Classé Bordeaux, but the best examples can be equally noble, if quietly so.

The flavors in a Chinon run the gamut from red and black berries to plums, white pepper, bramble, smoke, flint, leather, tangerine pith, sweet spice and earth. While there are no official hierarchies, the wines, mostly red, are understood as falling into two categories: the precocious ones, charming bistro wines, best served chilled and grown in the alluvial plane along the Vienne River; and the complex, structured wines grown in the clay, gravel and chalky tuffeau soils of the cliffs leading up the Loire Valley floor.

In the hands of the right vintner both can be engaging and lovely, but their character will undoubtedly reflect where they were grown. The more complex Chinons give the impression of being full-bodied, yet tend to be full in flavor rather than weight, especially when compared to cabernet sauvignon. Over the course of ten to thirty years, they will evolve from tannic with dark fruit flavors and hints of graphite and dried leaves, to something, soft, elegant, and perfumed. The quiet nobility of a fine Chinon is a direct result of this persistent arch toward refinement.

The good news about Chinon is that it is one of the few regions where the wine world’s trophy hunters and treasure hunters dine at the same trough. Collectible bottles from its most revered producers, the likes of Domaine Baudry, Domaine Olga Raffault, Domaine Breton, Domaine Philippe Alliet and Domaine Charles Joguet, can be found for as little as thirty dollars. Examples dating back two or three decades can be found for twice that amount. I am not sure why these wines present such a stunning value - maybe because there are no grand or premier cru designations, or because Chinon has become synonymous with simple wines served by the tumbler. Regardless, when friends say they want to start a wine collection, age worthy Chinons are precisely the kind of wines I suggest they seek out. They’re delicious and compelling without being too dear, and they’ll only get better if you forget about them for a couple of years.

If basic Chinon is bistro wine, then bottles from Baudry, Raffault, Breton, Alliet and Joguet are no doubt of the haut-bistro variety. Prized vineyards, attentive farming and traditional vinification elevate these wines into the realm of treasure hiding in plain site. Pair them with your favorite steak frites or recipes from Bouchon, the classic tome celebrating the haute-bistro cuisine of Thomas Keller’s Yountville restaurant. My go-to dish with these wines is the Poulet Rôti Forestière, Roast Chicken with a Ragout of Wild Mushrooms from the Bouchon cookbook (recipe below), which is remarkable for the way it evenly seasons the entire bird and encourages the skin to crisp and turn golden. It also may be the most accessible recipe Keller has ever published. It requires little more than soaking small chickens in a fragrant brine, roasting them at high heat and sautéing the garnish. The succulent flavorful meat and earthy chewy mushrooms are the perfect foils for the Chinon. Begin the meal with a rosé from the region, preferably from one of the producers above, and know that if you are lucky enough to have leftovers, both chicken and the Chinon will be better the next night.

10 Wines Chinon

Thomas Keller's Roast Chicken with a Ragout of Wild Mushrooms

Adapted from Bouchon, by Thomas Keller

Serves 4

For the Aromatic Brine

- 1 gallon water

- 1 cup kosher salt

- ¼ cup plus 2 tablespoons honey

- 12 bay leaves

- 2 tablespoons black peppercorns

- 3 rosemary sprigs

- 1 bunch thyme

- 1 bunch Italian parsley

- Grated zest and juice of 2 large lemons

Combine all the ingredients in a large pot, cover, and bring to a boil. Boil for 1 minute, stirring to dissolve the salt. Remove from the heat and cool before using.

For the Roast Chicken

- 2 tablespoons canola oil

- Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper

- Two 2 1/4 to 2 1/2-pound chickens. (you can substitute one or two 3 to 3 ½ pound chickens, each will serve three people.)

Preheat the oven to 475°F.

Rinse the chickens under cold water. Put the chickens in the pot of brine, weighting them with a plate if necessary to keep them submerged. Refrigerate for 6 hours, then remove the chickens from the brine (discard the brine), rinse them and pat them dry with paper towels. Season the insides with a light sprinkling of salt and pepper. Truss the chickens and let them sit at room temperature for 20 to 30 minutes before roasting. Meanwhile, prepare the jus (see recipe below).

Season the outside of the chickens with a light sprinkling of salt and pepper. Place one heavy ovenproof skillet, about 10 inches in diameter, for each chicken, over high heat. When the skillets are hot, add a tablespoon of canola oil to each one. When the oil is hot, put the birds breast size up in the skillets, and then into the oven with the legs facing the back of the oven. Roast for 40 minutes, checking the chickens every 15 minutes and rotating the skillets if they're roasting unevenly. After 40 minutes, check their temperature by inserting an instant-read thermometer between the leg and the thigh: the temperature should read approximately 155°F (the chicken will continue to cook as it sits, reaching a temperature of about 165°F). When the chickens are done, remove them from the oven, add the thyme leaves to the skillets and baste them several times with the pan juices and thyme leaves. Let sit in a warm spot for about 10 minutes.

For the Ragout of Wild Mushrooms

- 2 pounds assorted wild mushrooms

- 3 tablespoons canola oil

- 1 ½ teaspoons kosher salt

- 1 tablespoon unsalted butter

- 3 tablespoons minced shallots

- 1 tablespoon fresh thyme leaves

- ¾ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

- ¼ cup chicken jus (recipe below)

Keeping each type of mushroom separate, trim away any tough stems and tear larger mushrooms into smaller pieces. It is important to cook each type separately, since cooking time will vary. Divide the remaining ingredients proportionately according to the amount of each type of mushroom you have.

Coat a large sauté pan with a thin film of canola oil and place it over high heat. When the oil begins to smoke, add the first batch of mushrooms, season with salt, and sauté for a about a minute. The mushrooms will absorb the oil; they should not weep any liquid at this point. Add the appropriate amount of butter, shallots, thyme and black pepper, and sauté, tossing frequently until the mushrooms are tender, 2 to 4 minutes. Transfer the mushrooms to paper towels to drain. Wipe the pan out with a paper towel and cook the remaining mushrooms in batches.

When you are ready to serve the chicken, return the mushrooms to the skillet with a ¼ cup of chicken jus and bring the liquid to a simmer over medium-high heat. The wild mushroom ragout can be served family style in a bowl, or more formally in the center of a plate beneath the carved chicken as described below.

A Quick Chicken Jus

(This is a quick substitute for the home kitchen. Thomas Keller’s preparation for a classic chicken jus can be found on page 321 of the Bouchon cookbook)

- 1 tablespoon canola oil

- 1 chicken thigh, skin removed and fat trimmed

- Necks and wing tips of roasting chickens

- 2 carrots, peeled and chopped

- 1 celery stalk, peeled and chopped

- 1 shallot, peeled and chopped

- 4 cups water

- Kosher salt and fresh ground pepper

Coat a medium sauté pan with a thin film of canola oil and heat over medium-high heat. Add the chicken thigh, necks and wing tips to the pan. Sear for three minutes on each side, until golden. Add the carrots, celery and shallot and cook until the aromatics vegetables soften, stirring occasionally, about 5 minutes. Pour the water into the sauté pan, bring the water to a boil, then lower the heat, partially cover the pan with a lid, and let the broth simmer for an hour. Strain the broth through a mesh sieve into a small saucepan. Place the saucepan over medium-high heat, bring the broth to a boil and reduce the it until you have approximately one cup of jus. Season to taste with salt and pepper.

Assembly

The dish can be served on individual plates by ladling one quarter of the remaining jus onto four plates, arranging the mushrooms in the center, then placing two pieces of chicken over the mushrooms and garnishing with a sprig of parsley and a sprinkling of sea salt. Alternatively, it can be served family style on a large wooden platter. Arrange the mushrooms in the center and place the carved chicken pieces around the mushrooms, garnish with parsley and sea salt and pass the jus around the table in a small bowl with a ladle.

Summer Reds

When we talk about white wines for summers, we implicitly understand the reference. Summer whites are bright, light, thirst quenching wines that are eminently drinkable. Sancerre ,Muscadet Sevre-et-Maine and Albariño immediately come to mind. Summer reds are more difficult to define. We know we are not breaking out a pensive vintage Bordeaux for the family barbeque or uncorking a luscious California cabernet sauvignon with a bowl of chilled asparagus soup, but it is it possible to reduce the entire universe of reds to a simple rule of thumb for the summer months?

One helpful idea is to think about the climate of the wine’s region of origin. Warm climate reds tend to be juicy with plenty of body and just enough acidity to be mouthwatering. Think nero d’avola from Sicily, malbec from Mendoza, or grenache from the southern Rhone Valley. These intensely flavorful wines will maintain their structure in the face of bold, smoky, spicy summer fare.

On the other end of the spectrum are the cool climate reds, what we call bistro wines, since they show so well served lightly chilled by the carafe. At their best, cool climate reds are youthful and delicious, tasting of fresh berries often with floral or mineral notes. They won’t overwhelm a fresh salad niçoise, spring pea soup or chicken paillard. Some very fine examples can be found in the Loire Valley, notably the cabernet franc from Chinon and Saumur. Other sources worth seeking out are pinot noirs from Alsace and Central Otago.

- Alsace

- Amarone

- Architecture

- Assyrtiko

- Australia

- Austria

- Barbaresco

- Biodynamics

- Bolgheri

- Books

- Bordeaux

- Burgundy

- Cabernet Franc

- Cabernet Sauvignon

- California

- Champagne

- Chardonnay

- Chinon

- Cinsault

- Collecting

- Cycle of the Vine

- Dolcetto

- Entertaining

- France

- Gadgets

- Gigondas

- Greece

- Grenache

- Grüner Veltliner

- Holidays

- Hotel

- Importers

- Israel

- Italy

- Kamptaland

- Kosher

- Loire Valley

- Medoc

- Merlot

- Mouvedre

- Napa

- Nebbiolo

- Nero d'Avola

- News

- Pairings

- Pessac-Léognan

- Piedmont

- Pinot Noir

- Pomerol

- Pommard